For a talk I gave a week or so ago, I made some more interest-rate graphs. This extends the

last post on the subject. It also might be useful if you're teaching forward rates and expectations hypothesis.

The question: Are interest rates going up or down, especially long term rates? Investors obviously care, they want to know whether they should put money in long term bonds vs. short term bonds. As one who worries about debt and inflation, I'm also sensitive to the criticism that market rates are very low, forecasting apparently low rates for a long time. Yes, markets never see bad times coming, and markets 3 years ago got it way wrong thinking rates would be much higher than they are today (see

last post) but still, markets don't seem to worry.

But rather than talk, let's look at the numbers. I start with the forward curve. The forward rate is the "market expectation" of interest rates, in that it is the rate you can contract today to borrow in the future. If you know better than the forward rate, you can make a lot of money.

Here, I unite the recent history of interest rates together with forecasts made from today's forward curve. The one year rate (red) is just today's forward curve. I find the longer rates as the average of the forward curves on those dates. Today's forward curve is the market forceast of the future forward curve too, so to find the forecast 5 year bond yield in 2020, I take the average of today's forward rates for 2020, 2021,..2024.

I found it rather surprising just how much, and how fast, markets still think interest rates will rise. (Or, perhaps, how large the risk premium is. If you know enough to ask about Q measure or P measure, you know enough to answer your own question.)

How can the forecast rise faster than the actual long term yields? Well, remember that long yields are the average of expected future short rates, and if short rates are below today's 10 year rate for 5 years, then they must be above today's 10 year rate for another 5 years. So, it's a misconception to read from today's 2% 10 year rate that markets expect interest rates to be 2% in the future. Markets expect a rise to 4% within 10 years.

The forward curve has the nice property that if interest rates follow this forecast, then returns on bonds of all maturities are always exactly the same. The higher yields of long-term bonds exactly compensate for the price declines when interest rates rise. I graphed returns on bonds of different maturities here to make that point.

So, Mr. Bond speculator, if you believe the forecast in the first graph, it makes absolutely no difference whether you buy long or short. Otherwise, decide whether you think rates will rise faster or slower than the forward curve.

Now, let's think about other scenarios. One possibility is Japan. Interest rates get stuck at zero for a decade. This would come with sclerotic growth, low inflation, and a massive increase in debt, as it has in Japan. Eventually that debt is unsustainable, but as Japan shows, it can go on quite a long time. What might that look like?

Here is a "Japan scenario." I set the one year rate to zero forever. I only changed the level of the market forecast, however, not the slope. Thus, to form the expected forward curve in 2020, I shifted today's forward curve downwards so that the 2020 rate is zero, but other rates rise above that just as they do now.

This scenario is another boon to long term bond holders. They already got two big presents. Notice the two upward camel-humps in long term rates -- those were foreasts of rate risks that didn't work out, and people who bought long term bonds made money.

In a Japan scenario that happens again. Holders of long-term government bonds rejoice at their 2% yields. They get quite nice returns, shown left, as rates fail to rise as expected and the price of their bonds rises. Until the debt bomb explodes.

OK, what if things go the other way? What would an unexpectedly large

rise in interest rates look like?

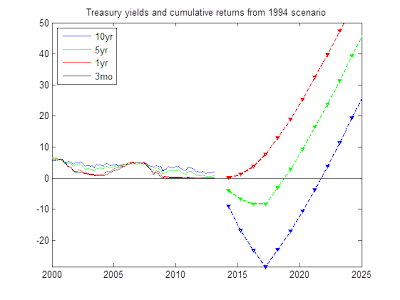

For example Feburary 1994 looked a lot like today, and then rates all of a sudden jumped up when the Fed started tightening.

To generate a 1994 style scenario from today's yields, I did the opposite of the Japan scenario. I took today's forward curve and added 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% to the one-year rate forecast. As with the Japan scenario, I shifted the whole forward curve up on those dates. We'll play with forward steepness in a moment.

Here are cumulative returns from the 1994 scenario. Long term bonds take a beating, of course. Returns all gradually rise, as interest rates rise. (These are returns to strategies that keep a constant maturity, i.e. buy a 10 year bond, sell it next year as a 9 year bond, buy a new 10 year bond, etc)

These have been fun, but I've only changed the level of the forward curve forecast, not the slope. Implicitly, I've gone along with the idea that the Fed controls everything about interest rates. If you worry, as I do, you worry that long rates can go up all on their own. Japan's 10 year rate has been doing this lately. When markets lose faith, long rates rise. Central bankers see "confidence" or "speculators" or "bubbles" or "conundrums." What does that look like?

To generate a "steepening" scenario, I imagined that markets one year from now decide that interest rates in 2017 will spike up 5 percentage points. This may be a "fear" not an "expectation," i.e. a rise in risk premium.

Then, the 5 and 10 year rates rise immediately, even though the Fed (red line) didn't do anything to the one-year rate. The bond market vigilantes stage a strike on long term debt.

Here are the consequences for cumulative returns of my steepening scenario. The long term bonds are hit much more than the shorter term bonds. This really is a bloodbath for 10 year and higher investors, leaving those under 5 years much less hurt.

So what will happen? I don't know, I don't make forecasts. But I do think it's useful to generate some vaguely coherent scenarios. The forward curve is not a rock solid this is what will happen forecast. The forward curve adds up all of these possiblities, with probabilities assigned to each, plus risk premium. There is a lot of uncertainty, and good portfolio formation starts with risk management not chasing alpha.