Europe's unemployment rate increased once more -- now at 12.2 percent. This is the highest level since data collection on European unemployment began in 1995. Expect new records ahead.

Too bad if you are young and live in Europe. The unemployment rate is above 25 percent for those under age 25 almost everywhere in Europe and is well above 40 percent in places like Spain and Italy (lets not talk about Greece...their data, at this point, is probably suspect).

Meanwhile, the IMF has noticed that taxpayer bailouts mainly enrich hedge funds. Why? Because after sovereign debt collapses in price, hedge funds come in and buy it for 20 cents on the dollar and then sit back to wait for the bailout. So, who wins. The average taxpayer simply transfers large amounts of private wealth into the coffers of rich hedge fund tycoons. Great policy!

It is now dawning on the IMF that restructuring sovereign debt (meaning a controlled bankruptcy) is a far better idea. It puts the losses where the losses belong and doesn't end up using taxpayer wealth to subsidize hedge funds. Wonder what took the IMF so long to understand what has been painfully obvious since this whole process began?

The assumption that Europe's problems were temporary and could be solved by taxpayer bailouts was an absurd assumption. Just one look at European government spending and government revenues would convince anyone with a modicum of common sense that Europe's debts are unpayable. There is no way out by the simple expedient of 'temporary' bailouts. The numbers don't work and the sooner that is acknowledged the better.

Now that hundreds of billions of Euros of ordinary Europeans citizens' wealth has been siphoned off into the pockets of hedge funds by these absurd bailout policies, the IMF shows signs of waking up. It's a bit too late, unfortunately. Europe's problems are now far worse. If Greece has been permitted to default on their sovereign debt four years ago, Europe would now be in a much better place. But, politicians stepped in.

The only way to reform Europe is to begin the process of controlled bankruptcies across the entire Eurozone. It will be painful. But, there is no choice. Europe will end up with either a controlled bankruptcy or an uncontrolled bankruptcy. That's the real choice.

Friday, May 31, 2013

Thursday, May 30, 2013

The Significance of the Smithfield Acquisition

Chinese food giant Shuanhui announced the purchase of Smithfield Foods this week. This is a salient example of a process that has been underway for many years.

If one country has a 40 percent savings rate and another country has a zero percent savings rate, the country with the larger savings rate will, in time, buy all of the assets of the country with a zero savings rate. That process is underway.

The US has had no net savings for several decades. The reason for the absence of savings is twofold: 1) the private sector doesn't save because most Americans see no need; after all, the government guarantees income security and health care into old age (social security, medicare, medicaid); why bother to save (the Obama administration's recent suggestion to begin taxing IRA's provides some additional reasons for Americans to avoid saving); 2) the government sector is a big, big dissaver (that's what fiscal deficits are all about).

But America has investment spending. Who provides the savings for this? Foreigners. Foreigners pay for this by buying up US assets. Every year that passes, Americans own a smaller percentage of American stocks, American housing, American office buildings, etc. Eventually, we will own nothing in this country.

Government policies that actively discourage savings work. They are working now. (Obama policies that actively discourage hiring work as well. They are working now. You get what you encourage and you lose what you discourage).

If one country has a 40 percent savings rate and another country has a zero percent savings rate, the country with the larger savings rate will, in time, buy all of the assets of the country with a zero savings rate. That process is underway.

The US has had no net savings for several decades. The reason for the absence of savings is twofold: 1) the private sector doesn't save because most Americans see no need; after all, the government guarantees income security and health care into old age (social security, medicare, medicaid); why bother to save (the Obama administration's recent suggestion to begin taxing IRA's provides some additional reasons for Americans to avoid saving); 2) the government sector is a big, big dissaver (that's what fiscal deficits are all about).

But America has investment spending. Who provides the savings for this? Foreigners. Foreigners pay for this by buying up US assets. Every year that passes, Americans own a smaller percentage of American stocks, American housing, American office buildings, etc. Eventually, we will own nothing in this country.

Government policies that actively discourage savings work. They are working now. (Obama policies that actively discourage hiring work as well. They are working now. You get what you encourage and you lose what you discourage).

Saturday, May 25, 2013

Anaphylaxis

My daughter Sally is at the Grand Central Academy of Art in New York. This is one of her still lives (yes, it's a painting). See if you can figure out what it means. Then click on the figure for an explanation. Don't miss "ceci n’est pas une molécule d’histamine."

Yes, this has nothing to do with economics. It's just cool.

Yes, this has nothing to do with economics. It's just cool.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

The Fed and Shadow Banking

The WSJ has a fascinating Op-Ed by Andy Kessler, "The Fed Squeezes the Shadow-Banking System" Andy thinks that Quantiative Easing has the opposite, contractionary effect.

QE is just a huge open market operation. The Fed buys Treasury securities and issues bank reserves instead. Why does this do anything? Why isn't this like trading some red M&Ms for some green M&Ms and expecting it to affect your weight? (M&M of course stands for "Modigliani Miller" if you didn't get the joke.)

The usual thinking is that bank reserves are "special." They are connected to GDP in a way that Treasuries are not. In the conventional monetary view, MV = PY. Bank reserves, through a multiplier, control M. The bank or credit channel view says that bank reserves control lending and lending affects PY. The red M&Ms, though superficially identical, have more calories.

In Andy's view (my interpretation), that is turned around now. Now, Treasuries supply more "liquidity" needs than bank reserves, and (more importantly) the supply of treasuries is more connected to nominal GDP than is the supply of bank reserves.

Part of this inversion of roles is supply. In place of the usual $50 billion, we have $3 trillion or so bank reserves. Bank reserves can only be used by banks, so they don't do much good for the rest of us. Now, they just sit as bank assets in place of mortgages or treasuries and don't make a difference to anything. More treasuries, according to Andy, we can do something with.

More deeply, constraints only go one way. Normally, the banking system is up against a constraint. Reserves pay less interest than other assets, so banks use as little as possible. Now, they are awash in liquidity. You can't push on a string, as the saying goes. Much "constraint" economics forgets that once the constraint is off, the relationship doesn't hold any more.

Andy describes the repo market and the sense in which Treasuries are "special" in providing low-haircut collateral. Lots of academic research is now viewing Treasuries as special or liquidity-providing in the shadow banking system.

So, this is at least a gorgeous possibility: In a frictionless world, open-market operations, buying one kind of government debt (Treasuries) and issuing another (reserves) have zero effect on anything, by the M&M theorem. Monetary economics thinks the M&M theorem is violated, because one kind of government debt (M) is connected to nominal GDP and the other is not.

But financial systems change. When the textbooks were written, banks mattered a lot, so bank reserves, leveraged to loans and checking accounts, were the "special" asset. In today's market, and given today's glut of reserves, Treasuries, leveraged to mortgage backed securities and money market funds through the repo market and "shadow banking system," might be the "special" asset connected to nominal GDP. In that case, the effects of open market operations might have the opposite sign. As Andy says,

You repo a security so that you can borrow against it. For example, you might buy a mortgage-backed security, then leave (repo, really) that security as collateral for a loan, which you used to buy the security in the first place. But what sense does it make to repo-finance a Treasury? You can't borrow at lower interest rate to make money on a Treasury! You could, possibly, if it's a long term Treasury and you're borrowing short, betting that interest rates don't rise. But I would think an interest rate swap or future would be a cheaper way to make that bet, and anyway betting on the slope of Treasury yield curve doesn't add up to the necessary GDP-linked lending that Andy has in mind.

In short, if you have money to buy a Treasury, why do you need to borrow? For any of this to get off the ground, you have to have some other, not totally rational, reason for buying the Treasury, and then you want to borrow against the Treasury so you can buy the risky asset that you really wanted all along. Who is that? Why is this such a necessary part of our financial system? Can't we fix things so they just buy the MBS with their initial cash?

Andy points out that repos are re-hypothecated. You use your Treasury as collateral against a loan, then the guy you gave it to uses it again as collateral to get the money to give to you. So one Treasury is used as collateral against two or three loans. Hmm. As the money multiplier creates run-prone structures, so using the same thing as collateral two or three times is a lot of what makes banks "too big to fail." If we all go down, who has the collateral?

A system awash in all kinds of liquidity, following the Freidman optimal quantity of money, seems a lot safer to me. I'd rather we expand the "bank reserve" concept -- fixed-value, floating-rate, electronically-transferable Treasury debt, and lots of it, washing the shadow banking system in liquidity and putting the run-prone structures out of business. Of course, open market operations would then have no effect in my world either, as I have removed the liquidity constraint in the shadow banking system just as Mr. Bernanke has removed it in the conventional banking system. But violations of M&M always mean the system can be made better.

If you want to comment and explain shadow banking, please use little words that the rest of us can understand.

QE is just a huge open market operation. The Fed buys Treasury securities and issues bank reserves instead. Why does this do anything? Why isn't this like trading some red M&Ms for some green M&Ms and expecting it to affect your weight? (M&M of course stands for "Modigliani Miller" if you didn't get the joke.)

The usual thinking is that bank reserves are "special." They are connected to GDP in a way that Treasuries are not. In the conventional monetary view, MV = PY. Bank reserves, through a multiplier, control M. The bank or credit channel view says that bank reserves control lending and lending affects PY. The red M&Ms, though superficially identical, have more calories.

In Andy's view (my interpretation), that is turned around now. Now, Treasuries supply more "liquidity" needs than bank reserves, and (more importantly) the supply of treasuries is more connected to nominal GDP than is the supply of bank reserves.

Part of this inversion of roles is supply. In place of the usual $50 billion, we have $3 trillion or so bank reserves. Bank reserves can only be used by banks, so they don't do much good for the rest of us. Now, they just sit as bank assets in place of mortgages or treasuries and don't make a difference to anything. More treasuries, according to Andy, we can do something with.

More deeply, constraints only go one way. Normally, the banking system is up against a constraint. Reserves pay less interest than other assets, so banks use as little as possible. Now, they are awash in liquidity. You can't push on a string, as the saying goes. Much "constraint" economics forgets that once the constraint is off, the relationship doesn't hold any more.

Andy describes the repo market and the sense in which Treasuries are "special" in providing low-haircut collateral. Lots of academic research is now viewing Treasuries as special or liquidity-providing in the shadow banking system.

So, this is at least a gorgeous possibility: In a frictionless world, open-market operations, buying one kind of government debt (Treasuries) and issuing another (reserves) have zero effect on anything, by the M&M theorem. Monetary economics thinks the M&M theorem is violated, because one kind of government debt (M) is connected to nominal GDP and the other is not.

But financial systems change. When the textbooks were written, banks mattered a lot, so bank reserves, leveraged to loans and checking accounts, were the "special" asset. In today's market, and given today's glut of reserves, Treasuries, leveraged to mortgage backed securities and money market funds through the repo market and "shadow banking system," might be the "special" asset connected to nominal GDP. In that case, the effects of open market operations might have the opposite sign. As Andy says,

... the Federal Reserve's policy—to stimulate lending and the economy by buying Treasurys..—is creating a shortage of safe collateral, the very thing needed to create credit in the shadow banking system for the private economy. The quantitative easing policy appears self-defeating, perversely keeping economic growth slower and jobs scarcer.I'm not totally convinced, though this story and the alleged enormous demand for Treasuries is being bandied around as established fact. I'm also not convinced that this is all a good idea. Maybe the Fed should starve the shadow banking system.

You repo a security so that you can borrow against it. For example, you might buy a mortgage-backed security, then leave (repo, really) that security as collateral for a loan, which you used to buy the security in the first place. But what sense does it make to repo-finance a Treasury? You can't borrow at lower interest rate to make money on a Treasury! You could, possibly, if it's a long term Treasury and you're borrowing short, betting that interest rates don't rise. But I would think an interest rate swap or future would be a cheaper way to make that bet, and anyway betting on the slope of Treasury yield curve doesn't add up to the necessary GDP-linked lending that Andy has in mind.

In short, if you have money to buy a Treasury, why do you need to borrow? For any of this to get off the ground, you have to have some other, not totally rational, reason for buying the Treasury, and then you want to borrow against the Treasury so you can buy the risky asset that you really wanted all along. Who is that? Why is this such a necessary part of our financial system? Can't we fix things so they just buy the MBS with their initial cash?

Andy points out that repos are re-hypothecated. You use your Treasury as collateral against a loan, then the guy you gave it to uses it again as collateral to get the money to give to you. So one Treasury is used as collateral against two or three loans. Hmm. As the money multiplier creates run-prone structures, so using the same thing as collateral two or three times is a lot of what makes banks "too big to fail." If we all go down, who has the collateral?

A system awash in all kinds of liquidity, following the Freidman optimal quantity of money, seems a lot safer to me. I'd rather we expand the "bank reserve" concept -- fixed-value, floating-rate, electronically-transferable Treasury debt, and lots of it, washing the shadow banking system in liquidity and putting the run-prone structures out of business. Of course, open market operations would then have no effect in my world either, as I have removed the liquidity constraint in the shadow banking system just as Mr. Bernanke has removed it in the conventional banking system. But violations of M&M always mean the system can be made better.

If you want to comment and explain shadow banking, please use little words that the rest of us can understand.

Labels:

Commentary,

Inflation,

Monetary Policy

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

Epstein on the IRS and more

Richard Epstein has a lovely essay, "The Real Lesson of the IRS Scandal" As lots of commentators left and right are realizing, this kind of outcome is baked in to our regulatory system. A small excerpt:

I think the point is larger still. The ACA (Obamacare) under Health and Human Services and financial regulation under the Dodd-Frank act are even more stark instances of the phenomenon. The regulations are immense, vague, contradictory, and demand discretionary approval by regulators. For a company to speak out against those acts is very dangerous.

India's sclerosis was once described as the "permit raj." That describes our future well.

But at least Americans are still outraged at this sort of thing. At least, unlike most other over-regulated countries, regulatory discretion is still traded for political support, not suitcases full of cash. However, what Epstein makes clear is, a witch-hunt at the IRS won't solve the problem.

The larger answer here seems pretty clear to me too. Why do we have tax-exempt status for any political groups? Actually, why do we have tax-exempt status for any groups at all? It's easy to be a non-profit -- just don't make any money. When you look at what a lot of "non-profits" do, how efficiently their money is used, the idea that we should be subsidizing most of them seems pretty silly. If we chucked out the whole tax-exempt business entirely, and allowed people to give money to any group they feel like giving it to without tax preference one way or another, the whole temptation for the IRS to hand out this subsidy in nefarious ways would vanish.

The dismal performance of the IRS is but a symptom of a much larger disease which has taken root in the charters of many of the major administrative agencies in the United States today: the permit power. Private individuals are not allowed to engage in certain activities or to claim certain benefits without the approval of some major government agency. The standards for approval are nebulous at best, which makes it hard for any outside reviewer to overturn the agency’s decision on a particular application.Richard goes on to skewer the FCC, the EPA, and the FDA. The fight over approval of liquid natural gas exports, which Richard doesn't mention is a perfect example.

That power also gives the agency discretion to drag out its review, since few individuals or groups are foolhardy enough to jump the gun and set up shop without obtaining the necessary approvals first. It takes literally a few minutes for a skilled government administrator to demand information that costs millions of dollars to collect and that can tie up a project for years. That delay becomes even longer for projects that need approval from multiple agencies at the federal or state level, or both.

The beauty of all of this (for the government) is that there is no effective legal remedy. Any lawsuit that protests the improper government delay only delays the matter more. Worse still, it also invites that agency (and other agencies with which it has good relations) to slow down the clock on any other applications that the same party brings to the table. Faced with this unappetizing scenario, most sophisticated applicants prefer quiet diplomacy to frontal assault, especially if their solid connections or campaign contributions might expedite the application process. Every eager applicant may also be stymied by astute competitors intent on slowing the approval process down, in order to protect their own financial profits. So more quiet diplomacy leads to further social waste.

I think the point is larger still. The ACA (Obamacare) under Health and Human Services and financial regulation under the Dodd-Frank act are even more stark instances of the phenomenon. The regulations are immense, vague, contradictory, and demand discretionary approval by regulators. For a company to speak out against those acts is very dangerous.

India's sclerosis was once described as the "permit raj." That describes our future well.

But at least Americans are still outraged at this sort of thing. At least, unlike most other over-regulated countries, regulatory discretion is still traded for political support, not suitcases full of cash. However, what Epstein makes clear is, a witch-hunt at the IRS won't solve the problem.

The larger answer here seems pretty clear to me too. Why do we have tax-exempt status for any political groups? Actually, why do we have tax-exempt status for any groups at all? It's easy to be a non-profit -- just don't make any money. When you look at what a lot of "non-profits" do, how efficiently their money is used, the idea that we should be subsidizing most of them seems pretty silly. If we chucked out the whole tax-exempt business entirely, and allowed people to give money to any group they feel like giving it to without tax preference one way or another, the whole temptation for the IRS to hand out this subsidy in nefarious ways would vanish.

Local Austerity

The Wall Street Journal had a really heart-warming article, Europe's Recession Sparks Grass-Roots Political Push about groups taking over local governments in southern Europe, and cleaning out years of mismanagement. An excerpt

At her inauguration Ms. Biurrun [the new mayor of Torroledones, Spain] choked up before a jubilant crowd.Great, no?

Then she began slashing away. She lowered the mayor's salary by 21%, to €49,500 a year, trimmed council members' salaries and eliminated four paid advisory positions.

She got rid of the police escort and the leased car, and gave the chauffeur a different job. She returned a carpet, emblazoned with the town seal, that had cost nearly €300 a month to clean. She ordered council members to pay for their own meals at work events instead of billing the town.

"I was so indignant seeing what these people had been doing with everyone's money as if it were their own," Ms. Biurrun said.

Those cuts, combined with savings achieved by renegotiating contracts for garbage pickup and other services, helped give a million-euro boost to the city treasury in her first year in office.

But wait, isn't this all "austerity?" Isn't cutting spending exactly the kind of thing that Keynesian macroeconomists, as well as the reigning IMF-style policy consensus decries, saying we need stimulus now, austerity later?

Keynesian, and especially new-Keynesian economics wants more government spending, even if completely wasted. Those trimmed salaries, fired "advisers," cleaning bills, restaurant spending, overpaid contracts are, in the standard mindset, all crucial for "demand" and goosing GDP. If stimulus advocates were at all honest, they would be writing blog posts decrying Ms. Birrun and her kind.

Of course they don't. Abstract "spending" sounds good, and touting abstract "topsy-turvy" model predictions sounds fine. But when it is concrete, it's so patently absurd that you don't hear it.

The Greek city of Thessaloniki cut costs after Yannis Boutaris, a businessman-turned-politician, took office in late 2010 and ended City Hall's relationship with a few selected providers. Competitive bidding has saved the city 80% of its previous spending on accounting, 25% on waste disposal trucks and 20% on printer paper. The savings have allowed Mr. Boutaris to spend more on social services, even while cutting taxes and paying down City Hall's debt to suppliers.How sad. So much "demand"-destroying "austerity."

(Of course, the main point of the articles is about a political realignment, in which local governments are becoming responsive to local voters, transparent, and efficient, rather than being cronyist machines of national political parties. I can't imagine anyone not feeling warm about that!)

Update: Courtesy Marginal Revolution, I found this nice story about the new Spanish $680 million submarine that will sink if put in water. MR snarkily asks "did this help Spain or hurt Spain." $680 million of government spending raises Spanish GDP by nearly $1 billion, so this is great, right?

Monday, May 20, 2013

Hitchhiking across America: embracing optionality and risk

Have you ever wanted to spend a month hitchhiking your way across country, or see the American landscape pass by from the inside of a freight train boxcar?

In the Vice documentary series, How to Hitchhike Across America: Thumbs Up, artist David Choe and his friend/nephew Harry Kim show us how to do just that.

Note: You can watch the full series by clicking through to the next episode link at the end of each clip.

I started watching this series on YouTube without any real expectations and was sucked in. The two start off hopping a freight train out of Los Angeles. As they make their way, slowly, to Las Vegas, we hear a bit of back story on David's life and their immediate plans for the trip.

While I won't give away all the details of their trip, I will say this: only in America can you hop out of a freight train boxcar and walk right over to your comped room at the Venetian.

Now, what I didn't know until after I started watching is that David Choe is a rather well-known graffiti artist and painter. In fact, back in 2005 Choe was hired by Sean Parker to paint some "graphic" murals on the walls of Facebook's first Silicon Valley office. David took company stock in lieu of cash for his efforts. Those shares were worth $200 million at the time of Facebook's IPO (about 5 years after this series aired).

As you watch David and Harry make their way across country, you begin to notice a theme. Aside from their most immediate concerns - finding a place to sleep, hitching a ride to the next town - there is no preplanned structure to their days. If the guys see an opportunity to have some fun or meet someone new, they take it.

Sure, there's a great deal of risk in this style of travel. When they're not avoiding cops or railway security guards, the guys discuss their fears of being mugged or raped, while also acknowledging the fear most drivers have of them. It's not easy hitching a ride from strangers in a time when, as one of their new pals offers, "the media has us scared of each others' shadows".

David and Harry and their fellow travelers have embraced these risks and try to meet them as best they can, while opening their lives to a sense of freedom and optionality. They go where they want and they can take the odd detour on their way if they so choose. In this, they might find approval from Antifragile author, Nassim Taleb, who argues for an anti-fragile world of "many highway exits and options" (more on that here).

While I watched their (well-edited) adventure unfold, I wondered about the benefits of such of a lifestyle. Although these two can probably choose to dip in and out of the hobo life at will, maybe they're gaining an insight into America, and life, that some of us may never have. Is it possible their serendipitous travels and approach to life might open up opportunities that may never have come if they were shackled to their work desk or stuck inside a corporate office?

While we ponder that, I'll leave you with this quote (thanks Wikipedia!):

Your life is your own unique canvas. Try to paint something you'd want to see.

In the Vice documentary series, How to Hitchhike Across America: Thumbs Up, artist David Choe and his friend/nephew Harry Kim show us how to do just that.

Note: You can watch the full series by clicking through to the next episode link at the end of each clip.

I started watching this series on YouTube without any real expectations and was sucked in. The two start off hopping a freight train out of Los Angeles. As they make their way, slowly, to Las Vegas, we hear a bit of back story on David's life and their immediate plans for the trip.

While I won't give away all the details of their trip, I will say this: only in America can you hop out of a freight train boxcar and walk right over to your comped room at the Venetian.

Now, what I didn't know until after I started watching is that David Choe is a rather well-known graffiti artist and painter. In fact, back in 2005 Choe was hired by Sean Parker to paint some "graphic" murals on the walls of Facebook's first Silicon Valley office. David took company stock in lieu of cash for his efforts. Those shares were worth $200 million at the time of Facebook's IPO (about 5 years after this series aired).

As you watch David and Harry make their way across country, you begin to notice a theme. Aside from their most immediate concerns - finding a place to sleep, hitching a ride to the next town - there is no preplanned structure to their days. If the guys see an opportunity to have some fun or meet someone new, they take it.

Sure, there's a great deal of risk in this style of travel. When they're not avoiding cops or railway security guards, the guys discuss their fears of being mugged or raped, while also acknowledging the fear most drivers have of them. It's not easy hitching a ride from strangers in a time when, as one of their new pals offers, "the media has us scared of each others' shadows".

David and Harry and their fellow travelers have embraced these risks and try to meet them as best they can, while opening their lives to a sense of freedom and optionality. They go where they want and they can take the odd detour on their way if they so choose. In this, they might find approval from Antifragile author, Nassim Taleb, who argues for an anti-fragile world of "many highway exits and options" (more on that here).

While I watched their (well-edited) adventure unfold, I wondered about the benefits of such of a lifestyle. Although these two can probably choose to dip in and out of the hobo life at will, maybe they're gaining an insight into America, and life, that some of us may never have. Is it possible their serendipitous travels and approach to life might open up opportunities that may never have come if they were shackled to their work desk or stuck inside a corporate office?

While we ponder that, I'll leave you with this quote (thanks Wikipedia!):

"It has often been said that Choe's greatest artwork is his own life. As his friend Jason Jaworski explained, "For me, there is no artwork Dave or anyone can create that is capable of completely equalling the vast canvas of Dave's life, which he paints daily while simply living."

Your life is your own unique canvas. Try to paint something you'd want to see.

The Significance of the JP Morgan Fight

For the past 100 years, small investors and lower income Americans have been able to invest in public securities and make huge gains. No one with a diversified portfolio of American stocks today has a loss. More remarkable, anyone who has held on for twenty years or more has huge, huge gains. And this same statement is true for nearly all twenty year periods since the 1930s (eighty years ago).

The success of the public markets has provided a way for folks without access to financial acumen to take on capital risk and be successful. You would think such markets would be applauded.

Nope.

Here comes the left. First Sarbanes-Oxley was passed to make sure that small companies faces huge hurdles in taking their firms public. Then along came Dodd-Frank, a creature of the Obama Congress, that continued the process of crushing public companies with mounds of mind-boggling regulations.

The final coup d'etat is now underway in the JP Morgan struggle. If "shareholders" force JM Dimon out as Chairman of the Board of one of the most successful companies in world history (a company that has greatly enriched its shareholders), the public will pay the ultimate price.

And, who are these "shareholders" that would topple Dimon? They are the 'agents' who, in theory, represent shareholders -- trustees who run endowments, pension funds, foundations. The vast majority of these folks don't like free markets and seem upset by the prospect of lower middle income folks having a path to wealth through the public markets.

The real shareholders are workers and taxpayers who directly and indirectly provide the funding for these endowments, pensions funds and foundations. They have no say at all. They certainly wouldn't vote to lower their future retirement income, which is precisely the direction their trustees are pursuing. In the name of 'corporate governance reform,' these trustees are destroying the access that ordinary citizens have to public markets.

So, topple Dimon and crush public companies and bend them to your will. That is the plan of the leftists who dominate pension funds, endowments and foundations these days, That ordinary Americans and real shareholders will have to pay the price for this nonsense is the great tragedy.

Ultimately, if the public market can be crushed, ordinary Americans will be forced to look to the government for their retirement, assuming the government has anything left at that point.

The success of the public markets has provided a way for folks without access to financial acumen to take on capital risk and be successful. You would think such markets would be applauded.

Nope.

Here comes the left. First Sarbanes-Oxley was passed to make sure that small companies faces huge hurdles in taking their firms public. Then along came Dodd-Frank, a creature of the Obama Congress, that continued the process of crushing public companies with mounds of mind-boggling regulations.

The final coup d'etat is now underway in the JP Morgan struggle. If "shareholders" force JM Dimon out as Chairman of the Board of one of the most successful companies in world history (a company that has greatly enriched its shareholders), the public will pay the ultimate price.

And, who are these "shareholders" that would topple Dimon? They are the 'agents' who, in theory, represent shareholders -- trustees who run endowments, pension funds, foundations. The vast majority of these folks don't like free markets and seem upset by the prospect of lower middle income folks having a path to wealth through the public markets.

The real shareholders are workers and taxpayers who directly and indirectly provide the funding for these endowments, pensions funds and foundations. They have no say at all. They certainly wouldn't vote to lower their future retirement income, which is precisely the direction their trustees are pursuing. In the name of 'corporate governance reform,' these trustees are destroying the access that ordinary citizens have to public markets.

So, topple Dimon and crush public companies and bend them to your will. That is the plan of the leftists who dominate pension funds, endowments and foundations these days, That ordinary Americans and real shareholders will have to pay the price for this nonsense is the great tragedy.

Ultimately, if the public market can be crushed, ordinary Americans will be forced to look to the government for their retirement, assuming the government has anything left at that point.

Sunday, May 19, 2013

Why IRS Scandals Will Never End?

The tax laws and IRS enforcement efforts are guaranteed to result in political favoritism on a grand scale. Why? Because they are complicated and ambiguous.

The American people do not understand the tax laws in their own country. One suspects that tax specialists don't understand these laws either. That leaves a lot of latitude to regulators. They can pick and choose, as we now know that they did in recent years.

Every so-called tax reform simply puts more complicated things into the tax laws.

The income tax needs to be abolished. There is no generally agreed way to define income (that's the main reason why tax laws are so complex). Even value-added tax concepts suffer from problems of definition.

Better to go to a uniform national sales tax. That could be easily understood by all Americans. The only way a national sales tax could become problematic is if there were exceptions (for food, medicine, etc.). There should be no exceptions.

Imagine how much time and money could be saved by abolishing the IRS and substituting a national sales tax. You can always make equity arguments, of course, but simplicity and transparency would be of enormous benefit to the average American.

We could rent out the IRS headquarters to a charter school.

The American people do not understand the tax laws in their own country. One suspects that tax specialists don't understand these laws either. That leaves a lot of latitude to regulators. They can pick and choose, as we now know that they did in recent years.

Every so-called tax reform simply puts more complicated things into the tax laws.

The income tax needs to be abolished. There is no generally agreed way to define income (that's the main reason why tax laws are so complex). Even value-added tax concepts suffer from problems of definition.

Better to go to a uniform national sales tax. That could be easily understood by all Americans. The only way a national sales tax could become problematic is if there were exceptions (for food, medicine, etc.). There should be no exceptions.

Imagine how much time and money could be saved by abolishing the IRS and substituting a national sales tax. You can always make equity arguments, of course, but simplicity and transparency would be of enormous benefit to the average American.

We could rent out the IRS headquarters to a charter school.

Saturday, May 18, 2013

The Role of Monetary Policy, Revisited

I am giving a talk Thursday May 30, titled "The Role of Monetary Policy, Revisited." The event is at Booth's Gleacher Center in downtown Chicago, reception 4:30 and talk 5:15. It's part of a series of talks sponsored by the Becker-Friedman Institute.

The talk is based on an essay I'm working on, and will be presenting at a few central banks this summer. Once per generation we re-think what central banks do, can't do, should do, and shouldn't do. Milton Friedman's famous 1968 address marked the last big transition. I think, we are in a similar moment. I will look at the big picture in the same spirit. I'm aiming at a serious talk, grounded in academic research, but accessible.

Blog followers, students, colleagues, friends, and even glider pilots are most welcome. Please rsvp so they know how many people to plan for.

The event announcement invitation and rsvp links are here on the BFI webpage

There is also an event announcement and rsvp link on the Booth Alumni events webpage here.

The talk is based on an essay I'm working on, and will be presenting at a few central banks this summer. Once per generation we re-think what central banks do, can't do, should do, and shouldn't do. Milton Friedman's famous 1968 address marked the last big transition. I think, we are in a similar moment. I will look at the big picture in the same spirit. I'm aiming at a serious talk, grounded in academic research, but accessible.

Blog followers, students, colleagues, friends, and even glider pilots are most welcome. Please rsvp so they know how many people to plan for.

The event announcement invitation and rsvp links are here on the BFI webpage

There is also an event announcement and rsvp link on the Booth Alumni events webpage here.

Problems viewing this e-mail? View it in a browser. |

|

|

Friday, May 17, 2013

More Interest-Rate Graphs

For a talk I gave a week or so ago, I made some more interest-rate graphs. This extends the last post on the subject. It also might be useful if you're teaching forward rates and expectations hypothesis.

The question: Are interest rates going up or down, especially long term rates? Investors obviously care, they want to know whether they should put money in long term bonds vs. short term bonds. As one who worries about debt and inflation, I'm also sensitive to the criticism that market rates are very low, forecasting apparently low rates for a long time. Yes, markets never see bad times coming, and markets 3 years ago got it way wrong thinking rates would be much higher than they are today (see last post) but still, markets don't seem to worry.

But rather than talk, let's look at the numbers. I start with the forward curve. The forward rate is the "market expectation" of interest rates, in that it is the rate you can contract today to borrow in the future. If you know better than the forward rate, you can make a lot of money.

Here, I unite the recent history of interest rates together with forecasts made from today's forward curve. The one year rate (red) is just today's forward curve. I find the longer rates as the average of the forward curves on those dates. Today's forward curve is the market forceast of the future forward curve too, so to find the forecast 5 year bond yield in 2020, I take the average of today's forward rates for 2020, 2021,..2024.

I found it rather surprising just how much, and how fast, markets still think interest rates will rise. (Or, perhaps, how large the risk premium is. If you know enough to ask about Q measure or P measure, you know enough to answer your own question.)

How can the forecast rise faster than the actual long term yields? Well, remember that long yields are the average of expected future short rates, and if short rates are below today's 10 year rate for 5 years, then they must be above today's 10 year rate for another 5 years. So, it's a misconception to read from today's 2% 10 year rate that markets expect interest rates to be 2% in the future. Markets expect a rise to 4% within 10 years.

The forward curve has the nice property that if interest rates follow this forecast, then returns on bonds of all maturities are always exactly the same. The higher yields of long-term bonds exactly compensate for the price declines when interest rates rise. I graphed returns on bonds of different maturities here to make that point.

The forward curve has the nice property that if interest rates follow this forecast, then returns on bonds of all maturities are always exactly the same. The higher yields of long-term bonds exactly compensate for the price declines when interest rates rise. I graphed returns on bonds of different maturities here to make that point.

So, Mr. Bond speculator, if you believe the forecast in the first graph, it makes absolutely no difference whether you buy long or short. Otherwise, decide whether you think rates will rise faster or slower than the forward curve.

Now, let's think about other scenarios. One possibility is Japan. Interest rates get stuck at zero for a decade. This would come with sclerotic growth, low inflation, and a massive increase in debt, as it has in Japan. Eventually that debt is unsustainable, but as Japan shows, it can go on quite a long time. What might that look like?

Here is a "Japan scenario." I set the one year rate to zero forever. I only changed the level of the market forecast, however, not the slope. Thus, to form the expected forward curve in 2020, I shifted today's forward curve downwards so that the 2020 rate is zero, but other rates rise above that just as they do now.

This scenario is another boon to long term bond holders. They already got two big presents. Notice the two upward camel-humps in long term rates -- those were foreasts of rate risks that didn't work out, and people who bought long term bonds made money.

In a Japan scenario that happens again. Holders of long-term government bonds rejoice at their 2% yields. They get quite nice returns, shown left, as rates fail to rise as expected and the price of their bonds rises. Until the debt bomb explodes.

OK, what if things go the other way? What would an unexpectedly large rise in interest rates look like?

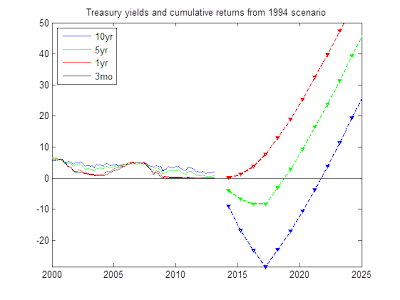

For example Feburary 1994 looked a lot like today, and then rates all of a sudden jumped up when the Fed started tightening.

To generate a 1994 style scenario from today's yields, I did the opposite of the Japan scenario. I took today's forward curve and added 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% to the one-year rate forecast. As with the Japan scenario, I shifted the whole forward curve up on those dates. We'll play with forward steepness in a moment.

Here are cumulative returns from the 1994 scenario. Long term bonds take a beating, of course. Returns all gradually rise, as interest rates rise. (These are returns to strategies that keep a constant maturity, i.e. buy a 10 year bond, sell it next year as a 9 year bond, buy a new 10 year bond, etc)

These have been fun, but I've only changed the level of the forward curve forecast, not the slope. Implicitly, I've gone along with the idea that the Fed controls everything about interest rates. If you worry, as I do, you worry that long rates can go up all on their own. Japan's 10 year rate has been doing this lately. When markets lose faith, long rates rise. Central bankers see "confidence" or "speculators" or "bubbles" or "conundrums." What does that look like?

To generate a "steepening" scenario, I imagined that markets one year from now decide that interest rates in 2017 will spike up 5 percentage points. This may be a "fear" not an "expectation," i.e. a rise in risk premium.

Then, the 5 and 10 year rates rise immediately, even though the Fed (red line) didn't do anything to the one-year rate. The bond market vigilantes stage a strike on long term debt.

Here are the consequences for cumulative returns of my steepening scenario. The long term bonds are hit much more than the shorter term bonds. This really is a bloodbath for 10 year and higher investors, leaving those under 5 years much less hurt.

So what will happen? I don't know, I don't make forecasts. But I do think it's useful to generate some vaguely coherent scenarios. The forward curve is not a rock solid this is what will happen forecast. The forward curve adds up all of these possiblities, with probabilities assigned to each, plus risk premium. There is a lot of uncertainty, and good portfolio formation starts with risk management not chasing alpha.

The question: Are interest rates going up or down, especially long term rates? Investors obviously care, they want to know whether they should put money in long term bonds vs. short term bonds. As one who worries about debt and inflation, I'm also sensitive to the criticism that market rates are very low, forecasting apparently low rates for a long time. Yes, markets never see bad times coming, and markets 3 years ago got it way wrong thinking rates would be much higher than they are today (see last post) but still, markets don't seem to worry.

But rather than talk, let's look at the numbers. I start with the forward curve. The forward rate is the "market expectation" of interest rates, in that it is the rate you can contract today to borrow in the future. If you know better than the forward rate, you can make a lot of money.

Here, I unite the recent history of interest rates together with forecasts made from today's forward curve. The one year rate (red) is just today's forward curve. I find the longer rates as the average of the forward curves on those dates. Today's forward curve is the market forceast of the future forward curve too, so to find the forecast 5 year bond yield in 2020, I take the average of today's forward rates for 2020, 2021,..2024.

I found it rather surprising just how much, and how fast, markets still think interest rates will rise. (Or, perhaps, how large the risk premium is. If you know enough to ask about Q measure or P measure, you know enough to answer your own question.)

How can the forecast rise faster than the actual long term yields? Well, remember that long yields are the average of expected future short rates, and if short rates are below today's 10 year rate for 5 years, then they must be above today's 10 year rate for another 5 years. So, it's a misconception to read from today's 2% 10 year rate that markets expect interest rates to be 2% in the future. Markets expect a rise to 4% within 10 years.

The forward curve has the nice property that if interest rates follow this forecast, then returns on bonds of all maturities are always exactly the same. The higher yields of long-term bonds exactly compensate for the price declines when interest rates rise. I graphed returns on bonds of different maturities here to make that point.

The forward curve has the nice property that if interest rates follow this forecast, then returns on bonds of all maturities are always exactly the same. The higher yields of long-term bonds exactly compensate for the price declines when interest rates rise. I graphed returns on bonds of different maturities here to make that point.So, Mr. Bond speculator, if you believe the forecast in the first graph, it makes absolutely no difference whether you buy long or short. Otherwise, decide whether you think rates will rise faster or slower than the forward curve.

Now, let's think about other scenarios. One possibility is Japan. Interest rates get stuck at zero for a decade. This would come with sclerotic growth, low inflation, and a massive increase in debt, as it has in Japan. Eventually that debt is unsustainable, but as Japan shows, it can go on quite a long time. What might that look like?

Here is a "Japan scenario." I set the one year rate to zero forever. I only changed the level of the market forecast, however, not the slope. Thus, to form the expected forward curve in 2020, I shifted today's forward curve downwards so that the 2020 rate is zero, but other rates rise above that just as they do now.

This scenario is another boon to long term bond holders. They already got two big presents. Notice the two upward camel-humps in long term rates -- those were foreasts of rate risks that didn't work out, and people who bought long term bonds made money.

In a Japan scenario that happens again. Holders of long-term government bonds rejoice at their 2% yields. They get quite nice returns, shown left, as rates fail to rise as expected and the price of their bonds rises. Until the debt bomb explodes.

OK, what if things go the other way? What would an unexpectedly large rise in interest rates look like?

For example Feburary 1994 looked a lot like today, and then rates all of a sudden jumped up when the Fed started tightening.

To generate a 1994 style scenario from today's yields, I did the opposite of the Japan scenario. I took today's forward curve and added 1%, 2%, 3% and 4% to the one-year rate forecast. As with the Japan scenario, I shifted the whole forward curve up on those dates. We'll play with forward steepness in a moment.

Here are cumulative returns from the 1994 scenario. Long term bonds take a beating, of course. Returns all gradually rise, as interest rates rise. (These are returns to strategies that keep a constant maturity, i.e. buy a 10 year bond, sell it next year as a 9 year bond, buy a new 10 year bond, etc)

These have been fun, but I've only changed the level of the forward curve forecast, not the slope. Implicitly, I've gone along with the idea that the Fed controls everything about interest rates. If you worry, as I do, you worry that long rates can go up all on their own. Japan's 10 year rate has been doing this lately. When markets lose faith, long rates rise. Central bankers see "confidence" or "speculators" or "bubbles" or "conundrums." What does that look like?

To generate a "steepening" scenario, I imagined that markets one year from now decide that interest rates in 2017 will spike up 5 percentage points. This may be a "fear" not an "expectation," i.e. a rise in risk premium.

Then, the 5 and 10 year rates rise immediately, even though the Fed (red line) didn't do anything to the one-year rate. The bond market vigilantes stage a strike on long term debt.

Here are the consequences for cumulative returns of my steepening scenario. The long term bonds are hit much more than the shorter term bonds. This really is a bloodbath for 10 year and higher investors, leaving those under 5 years much less hurt.

So what will happen? I don't know, I don't make forecasts. But I do think it's useful to generate some vaguely coherent scenarios. The forward curve is not a rock solid this is what will happen forecast. The forward curve adds up all of these possiblities, with probabilities assigned to each, plus risk premium. There is a lot of uncertainty, and good portfolio formation starts with risk management not chasing alpha.

Labels:

Finance,

Inflation,

Monetary Policy,

Talks

Doctor-owned hospitals

In writing about the ACA and our health-care problems, I started to think more and more about supply restrictions. In every other industry, costs come down when new suppliers come in and compete. Yet our health-care system is full of restrictions and protections to keep new suppliers out, and competition down. Then we wonder why hospitals won't tell you how much care will cost, and send you bills with $100 band aids on them.

In that context, I was interested to learn this week about the ACA's limits on expansion of doctor-owned hospitals. The Wall Street Journal article is here, and I found interesting coverage in American Medical News. The text and analysis of the amazing section 6001 of the ACA is here

In astouding (to me) news, the ACA prohibits doctor-owned hospitals from expanding, and prevents new doctor-owned hospitals at all, if they are going to serve Medicare or Medicaid patients. From WSJ

As a reader of this blog might expect, for-profit institutions, run by crucial employees, are run efficiently, make money and serve their customers

In related news, what's with the crazy hospital bills which nobody pays? A New York Times article has two tidbits.

In that context, I was interested to learn this week about the ACA's limits on expansion of doctor-owned hospitals. The Wall Street Journal article is here, and I found interesting coverage in American Medical News. The text and analysis of the amazing section 6001 of the ACA is here

In astouding (to me) news, the ACA prohibits doctor-owned hospitals from expanding, and prevents new doctor-owned hospitals at all, if they are going to serve Medicare or Medicaid patients. From WSJ

The Affordable Care Act aimed to end a boom in doctor-owned hospitals, a highly profitable niche known for its luxury facilities. Instead, many of the hospitals are wiggling around the federal health-care law's growth caps and even thriving.Only in medicine is "highly profitable niche known for its luxury facilities" a bad thing. Didn't the left like employee-owned companies, worker cooperatives and all that? And when is getting around silly restrictions "wiggling?" Et tu, WSJ?

The law, passed in 2010, blocked building any new physician-owned hospitals and prevented existing ones from adding beds or operating rooms in order to qualify for Medicare paymentsNow, let's see if it takes you more than 10 seconds to figure out the unintended consequences of this brilliant idea. Don't peek...

...to grow without running afoul of the rules, some of the country's roughly 275 doctor-owned hospitals are expanding their operating hours, increasing procedures in ways not restricted by the law and rejecting patients on Medicare...Then, some try to give up and do what the government wants....

"they are scheduling operations later and on weekends, instead of 7 a.m. to 5 p.m." North Cypress Medical Center outside Houston is building up practice areas, such as same-day surgeries, that don't require admitting patients overnight... Forest Park Medical Center in Dallas has stopped accepting Medicare patients, allowing it to escape the law's restrictions entirely.

The Surgical Institute of Reading in Pennsylvania tried to sell itself to a local community hospital. "We couldn't expand, but we thought a partnership would allow us to continue our practice," said its board chairman, Charles Lutz.Let's see, reorganizing so you are allowed to expand decreases competition? You just can't make this stuff up.

But the Federal Trade Commission blocked the merger, saying the sale would decrease competition and could lead to higher costs for patients and the government.

As a reader of this blog might expect, for-profit institutions, run by crucial employees, are run efficiently, make money and serve their customers

...many physician-owned hospitals have enjoyed 20% to 35% profit margins in recent years. U.S. community hospitals' profits hovered around 7% in 2010... new Medicare measurements showing that doctor-owned hospitals represent about half of the top 100 facilities whose performance will merit bonus Medicare reimbursements because of their cost efficiency and patient satisfaction.They even provide a

"5-star atmosphere" and a gourmet restaurant with a wine list and cigarsFrom American Medical news,

When the federal government sorted through the first round of clinical information it was using to reward hospitals for providing higher-quality care in December 2012, the No. 1 hospital on the list was physician-owned Treasure Valley Hospital in Boise, Idaho. Nine of the top 10 performing hospitals were physician-owned, as were 48 of the top 100.So why in the world does the government want to restrict them? WSJ:

But any effort to undo the expansion limits faces an uphill battle with Democrats, because the restrictions were a deal-breaker for hospitals when the White House sought their support for the law in 2009, industry lobbyists say.and AMN:

The American Hospital Assn. and the Federation of American Hospitals continue to back that section of the ACA. Several key lawmakers, including Senate Finance Committee Chair Max Baucus (D, Mont.) and panel member Chuck Grassley (R, Iowa), are in strong support of community hospitals in the debate.Aha. In return for political support for the ACA the major hospitals put in this blatant supply restriction against efficient competitors. And we wonder why health care is so expensive.

In related news, what's with the crazy hospital bills which nobody pays? A New York Times article has two tidbits.

Until a recent ruling by the Internal Revenue Service, ... a hospital could use the higher prices when calculating the amount of charity care it was providing, said Gerard Anderson, director of the Center for Hospital Finance and Management at Johns Hopkins. “There is a method to the madness, though it is still madness,” Mr. Anderson said.Aha. Quote $100 for a band-aid, and when the patient doesn't pay it, write it off as a tax loss. The next one is really clever.

To make money from Bayonne Medical, the new buyers made some big changes in the hospital’s business strategy.Really, does nobody every think for a minute, "Hmm, if we pass this law, what awful unintended consequences will it have?"

First, they converted Bayonne Medical from a nonprofit to a for-profit hospital...Next, they moved to sever existing contracts with large private insurers, essentially making Bayonne Medical an out-of-network hospital for most insurance plans.

Under New Jersey law, patients treated in a hospital emergency room outside their provider’s network have to pay out of pocket only what they would have paid if the hospital was in the network. But an out-of-network hospital can bill the patient’s insurer at essentially whatever rate it cares to set....

In recent years, Bayonne Medical put up digital billboards highlighting the short waits in its emergency rooms in an effort to attract more patients....

While the law was aimed at giving patients more hospitals to choose from, it “has had the unintended consequence of rewarding folks for these inflated charges,” said Wardell Sanders, president of the New Jersey Association of Health Plans...

Community leaders in Bayonne...said the buyers were always candid about the methods they intended to use to make the hospital a profitable enterprise.

Labels:

Health economics,

Regulation

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Meanwhile, On The Government Front

According to President Obama, we need more government.to provide 'fairness' for the American middle class. The latest series of scandals -- Benghazi, the AP snooping situations, and the IRS targeting of conservative groups, should serve to show why government is not likely to be the solution to the problem of getting the economy going again.

Government scandals are not new and are certainly not limited to the Democrats. Republicans are just as willing to bend government to their will as the Democrats. That's why government is not the proper place to put our trust. Our trust should belong in the free market, not in the bureaucrat, who may have another agenda.

Regulators can have a will of their own and it is very hard for the average citizen or company to fight them, especially when the regulators are willing to bend the law.

Free markets don't have political biases. Free markets are all about individuals trying to make a better life for themselves and their families through their own efforts.

Government is about taking from one person by force and giving to another. Those on the receiving end typically vote for politicians willing to do pretty much anything to demonize their opponents. Again, Republicans are just as likely to do this as Democrats.

Health care and pretty much every other endeavor should be provided in the free market. The government should butt out. By having medicare, medicaid and Obamacare, the US virtually guarantees that health care will be doled out according to the whims of the ascendant political party and the losers will pay and suffer the indignities of a disastrous health care system.

A good example of this is education. Look where government employees and politicians get their education. Then compare that to where the children of the middle class get their education. This is the outcome you get when government is providing the service.

Pretty much the same applies to all of the provisions of government services. The free market delivers best. The government, ultimately, is mainly a purveyor of corruption. Witness the current plight of the Obama Administration.

Government scandals are not new and are certainly not limited to the Democrats. Republicans are just as willing to bend government to their will as the Democrats. That's why government is not the proper place to put our trust. Our trust should belong in the free market, not in the bureaucrat, who may have another agenda.

Regulators can have a will of their own and it is very hard for the average citizen or company to fight them, especially when the regulators are willing to bend the law.

Free markets don't have political biases. Free markets are all about individuals trying to make a better life for themselves and their families through their own efforts.

Government is about taking from one person by force and giving to another. Those on the receiving end typically vote for politicians willing to do pretty much anything to demonize their opponents. Again, Republicans are just as likely to do this as Democrats.

Health care and pretty much every other endeavor should be provided in the free market. The government should butt out. By having medicare, medicaid and Obamacare, the US virtually guarantees that health care will be doled out according to the whims of the ascendant political party and the losers will pay and suffer the indignities of a disastrous health care system.

A good example of this is education. Look where government employees and politicians get their education. Then compare that to where the children of the middle class get their education. This is the outcome you get when government is providing the service.

Pretty much the same applies to all of the provisions of government services. The free market delivers best. The government, ultimately, is mainly a purveyor of corruption. Witness the current plight of the Obama Administration.

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

New high for the S&P 500: back up the mountain

We've reached a new all-time high on the S+P 500 (in nominal terms, anyway) with today's close of 1,658.78.

Four years from the March 2009 bottom, we're up nearly 1,000 points on the SPX. If we go back to the weekly close of 1,576 from the last bull market high (in October 2007), that's a 1,902 point round-trip in the S+P. We've gone down, and back up, the mountain in that time.

There has been broad participation in this latest move higher, with over 90% of S+P 500 stocks trading above their 200 day moving average. The trend is up and the market continues to climb the (increasingly global) wall of worry. Not to mention, as Ray Dalio learned some time ago, "currency depreciation and money printing are good for stocks".

Related posts:

1. Bonds vs. stocks: March 2009 - April 2013.

2. Lessons from Hedge Fund Market Wizards: Ray Dalio.

Four years from the March 2009 bottom, we're up nearly 1,000 points on the SPX. If we go back to the weekly close of 1,576 from the last bull market high (in October 2007), that's a 1,902 point round-trip in the S+P. We've gone down, and back up, the mountain in that time.

There has been broad participation in this latest move higher, with over 90% of S+P 500 stocks trading above their 200 day moving average. The trend is up and the market continues to climb the (increasingly global) wall of worry. Not to mention, as Ray Dalio learned some time ago, "currency depreciation and money printing are good for stocks".

Related posts:

1. Bonds vs. stocks: March 2009 - April 2013.

2. Lessons from Hedge Fund Market Wizards: Ray Dalio.

Labels:

Stocks

Are You Still Unhappy With Wall Street?

Those who invest in the US stock market have nothing to complain about. Stocks are on a tear in 2013 and have produced returns north of 8 percent annually over the past 100 years. What else does that well?

It has been almost impossible to avoid a lush retirement if one simply salted away money into an index fund regularly over the past 40 years.

So why do you continue to hear that Wall Street cannot be trusted and why do Congress and the Administration continue to try to crush Wall Street under a sea of litigation, regulation, and hyperbole.?

Will we really be better off without Wall Street? The average American has had the rare ability to simply plump his money down into an index fund and retire in splendor ($ 2,000 salted away in an IRA annually produced over $ 2 million in 40 years). I guess this kind of independence is too much for politicians to bear.

No one who has ever purchased an index fund at any time in history and still owns it today has a loss. In fact, it would be hard to find anyone who hasn't made an enormous amount of money in their index fund.

But, give Obama some time. Besides bludgeoning Wall Street into submission, his administration has sounded the first bugle in its war against IRAs.

Look for more of this. Obama will leave no stone unturned in his war against America's middle class. The war against Wall Street is designed, one supposes, to prohibit the average American from funding his retirement safely and force more Americans to fall back onto the US government for their retirement.

It has been almost impossible to avoid a lush retirement if one simply salted away money into an index fund regularly over the past 40 years.

So why do you continue to hear that Wall Street cannot be trusted and why do Congress and the Administration continue to try to crush Wall Street under a sea of litigation, regulation, and hyperbole.?

Will we really be better off without Wall Street? The average American has had the rare ability to simply plump his money down into an index fund and retire in splendor ($ 2,000 salted away in an IRA annually produced over $ 2 million in 40 years). I guess this kind of independence is too much for politicians to bear.

No one who has ever purchased an index fund at any time in history and still owns it today has a loss. In fact, it would be hard to find anyone who hasn't made an enormous amount of money in their index fund.

But, give Obama some time. Besides bludgeoning Wall Street into submission, his administration has sounded the first bugle in its war against IRAs.

Look for more of this. Obama will leave no stone unturned in his war against America's middle class. The war against Wall Street is designed, one supposes, to prohibit the average American from funding his retirement safely and force more Americans to fall back onto the US government for their retirement.

Friday, May 10, 2013

Jamie Dimon's Lament

Shareholders will vote soon. Right. Wrong. Shareholders typically have no idea that they are shareholders. Shareholders' agents -- pension funds, endowments, foundations, money managers -- these folks vote the shares, acting as agents for shareholders.

What do these agents think? They think that capitalism is fundamentally flawed and that corporations spend too much time seeking profit opportunities. Instead, public companies should be more concerned with 'activism.'

How does this help the ultimate shareholders? It makes them poorer. Retirement income is lowered and assets are frivolously wasted by the so-called agents.

But, what do the agents care. It doesn't affect them in the slightest.

In the name of corporate governance reform, these 'agents' are trying to impose an outside (of the company) Chairman of the Board for Citigroup, replacing Jamie Dimon and pushing Dimon to a subsidiary role. This would recreate the corporate governance structure that prevailed at Enron (and others) before they famously slid into a scandalous bankruptcy.

JP Morgan is one of the best performing large financial institutions in the world. Shareholders have been richly rewarded for the past five years by owning stock in JP Morgan. So, what to do?

Make a mountain out of a mole hill out of a $ 6 billion hedging loss by the great whale! What a waste of time! That loss did not keep JP Morgan from producing huge income and income growth, even in the same time period as the $ 6 billion loss!

So, what's the right answer? Decapitate JP Morgan. Maybe, we can create another Enron.

The move to replace JP Morgan as Chairman is anti-shareholder. If successful (and it will be ultimately), it will weaken JP Morgan, make retirees poorer and less able to cope financially, and enrich politicians and wealthy social activists (and their foundations and endowments). It will also serve to continue to undermine free markets and common sense.

What do these agents think? They think that capitalism is fundamentally flawed and that corporations spend too much time seeking profit opportunities. Instead, public companies should be more concerned with 'activism.'

How does this help the ultimate shareholders? It makes them poorer. Retirement income is lowered and assets are frivolously wasted by the so-called agents.

But, what do the agents care. It doesn't affect them in the slightest.

In the name of corporate governance reform, these 'agents' are trying to impose an outside (of the company) Chairman of the Board for Citigroup, replacing Jamie Dimon and pushing Dimon to a subsidiary role. This would recreate the corporate governance structure that prevailed at Enron (and others) before they famously slid into a scandalous bankruptcy.

JP Morgan is one of the best performing large financial institutions in the world. Shareholders have been richly rewarded for the past five years by owning stock in JP Morgan. So, what to do?

Make a mountain out of a mole hill out of a $ 6 billion hedging loss by the great whale! What a waste of time! That loss did not keep JP Morgan from producing huge income and income growth, even in the same time period as the $ 6 billion loss!

So, what's the right answer? Decapitate JP Morgan. Maybe, we can create another Enron.

The move to replace JP Morgan as Chairman is anti-shareholder. If successful (and it will be ultimately), it will weaken JP Morgan, make retirees poorer and less able to cope financially, and enrich politicians and wealthy social activists (and their foundations and endowments). It will also serve to continue to undermine free markets and common sense.

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Solar Panel Tariffs

It's time to start a new series on "energy idiocy." You just can't make this stuff up... From today's WSJ:

The US doesn't get to indulge in any Europe bashing here,

Of course it was a bit of a miracle that prices came down in the first place. Usually, subsidizing and protecting an industry in the idea that just making it bigger makes it cheaper leads to large inefficient industries. The correlation between big and cheap comes from competition. Hence revealing that it was the Chinese who figured out how to exploit European subsidies and actually make panels cheaper.

If you have any remaining thought that concern for the environment motivates any of this mania, reading between the lines of the rest of the story will put that to rest:

If we want to subsidize solar panel production (debateable, but "if") for environmental reasons, and if China decides to tax their citizens to provide the subsidies rather than us tax our citizens, the appropriate response is flowers, chocolates, and a nice thank-you card.

Update: Donald Boudreaux at Cafe Hayek did a much better job.

*Update: A reader catches me with possibly out-of-date facts. I'll leave his comment here and postpone getting in to a sidetrack about corn ethanol. I'll look in to it, as it seems a good topic for another "energy idiocy" post at some point.

BRUSSELS—Chinese solar-panel manufacturers will face import tariffs of up to 67.9% at European Union borders under a plan from the 27-nation bloc's executive body...Europe, like the US, subsidizes the installation of solar panels. So, we subsidize things to make the prices to consumers go down and encourage the industry. Then when the industry is encouraged and prices do go down, we pass tariffs to make prices go up. This is almost as fun as oil, which we subsidize to make prices go down, then pass regulations to try to stop people from using it.

The US doesn't get to indulge in any Europe bashing here,

The U.S. has already placed tariffs on solar-panel imports from China.We also subsidize ethanol, but only from midwestern corn. We have tariffs against ethanol from Brazilian sugar cane, which is a whole lot better environmentally (is a lot less closer to using 1 btu of petroleum to produce 1 btu of ethanol, wash away topsoil and fertilizers down the Mississippi, drive up corn prices)* but seems not to show up at the Iowa caucuses.

Of course it was a bit of a miracle that prices came down in the first place. Usually, subsidizing and protecting an industry in the idea that just making it bigger makes it cheaper leads to large inefficient industries. The correlation between big and cheap comes from competition. Hence revealing that it was the Chinese who figured out how to exploit European subsidies and actually make panels cheaper.

If you have any remaining thought that concern for the environment motivates any of this mania, reading between the lines of the rest of the story will put that to rest:

Suntech Power Holdings ..and its subsidiaries will face tariffs of 48.6%, according to the document. Tariffs on LDK Solar ... will be 55.9%, and tariffs on Trina Solar Ltd.... will be 51.5%. JingAo Solar Co. will face tariffs of 58.7%..The tariffs vary specifically company by company, and reward those that played along politically.

Most other Chinese companies in the sector that cooperated with the investigation will pay the average tariff of 47.6%. Those that didn't will pay a tariff of 67.9%, according to the document.

...European manufacturers have filed a separate complaint against the Chinese firms alleging they receive Chinese-government supportThey are shocked, shocked to find that subsidies and bailouts are occurring in the Chinese solar panel industry.

European import duties would deal a blow to these (Chinese) manufacturers, which have been piling up losses and struggling to refinance huge debts.

In March, Suntech sought bankruptcy protection in China, after defaulting on a $541 million bond repayment it owed mainly to Western investors.Western investors, who appaarently are not as well connected as the western investors in European solar panel plants.

LDK and Trina are both facing large debt repayments. LDK's hometown of Xinyu, China, bailed out the company in 2012, agreeing to repay $80 million of its debts.Here in the land of free markets, we never bail out large politically connected solar panel plants....

If we want to subsidize solar panel production (debateable, but "if") for environmental reasons, and if China decides to tax their citizens to provide the subsidies rather than us tax our citizens, the appropriate response is flowers, chocolates, and a nice thank-you card.

Update: Donald Boudreaux at Cafe Hayek did a much better job.

*Update: A reader catches me with possibly out-of-date facts. I'll leave his comment here and postpone getting in to a sidetrack about corn ethanol. I'll look in to it, as it seems a good topic for another "energy idiocy" post at some point.